WC’s last mayor a United Empire Loyalist

By Jake Davies - West Carleton Online

KINBURN – A six-month research project for Kinburn farmer Dwight Eastman has led to the discovery he is a United Empire Loyalist with family who fought for the British in the War of Independence.

Eastman, a well-known farmer and West Carleton’s last mayor and first city councillor following amalgamation, has spent the last half of the COVID-19 year researching his family history and developing an already established love for genealogy.

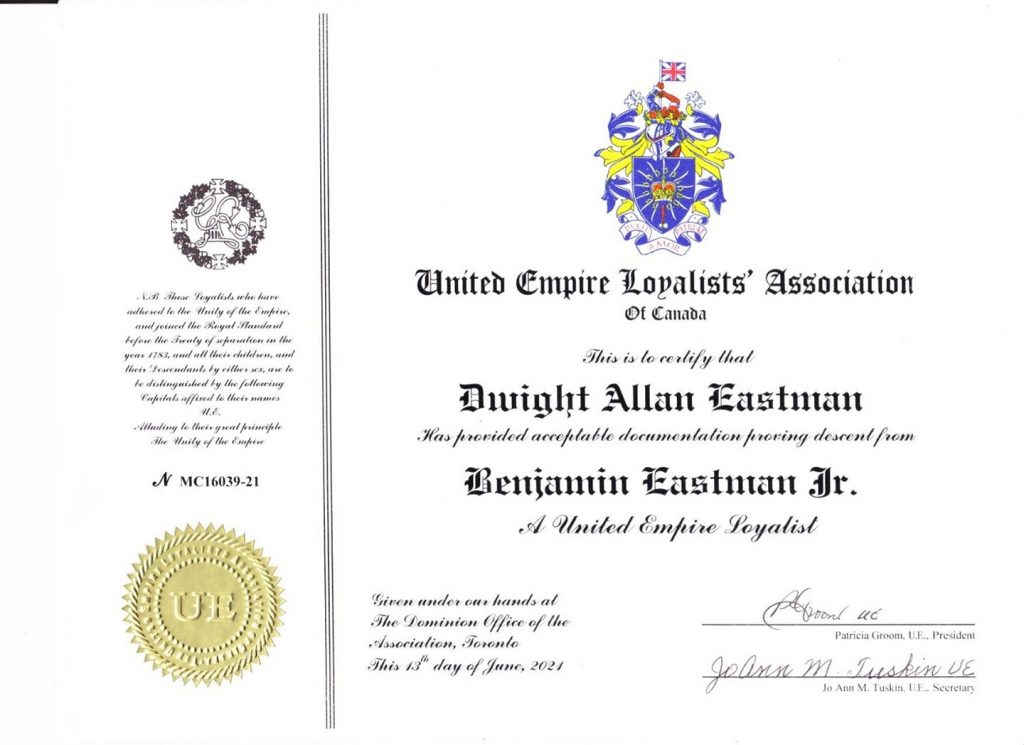

Eastman, who celebrated his 76th birthday on Aug. 12, took on the deep dive and his research led to him earning the United Empire Loyalist Certificate presented to him earlier this month. The certificate means Eastman provided the necessary documentation to be considered a verified descendant of United Empire Loyalists.

Eastman’s Loyalist roots dates back to January 1719, across the border in Morristown, New Jersey when Benjamin Eastman, Sr. was born.

Benjamin, Sr. was listed on the land rolls in the mid 1700s as a lumberman and shoemaker who was also a fighter and a Loyalist soldier. He enlisted in the British army when Marquis de Montcalm and his native allies began their assaults.

Benjamin, Sr. survived the siege of Fort William Henry on Lake George, New York in 1757 in the battle of the French-Indian War.

The British surrendered the fort and were put on a forced march to Fort Edward. British officers tried to win over the First Nation warriors with alcohol, but the warriors rampaged and murdered hundreds of the captives.

Benjamin, Sr. survived and hoped to leave war behind, but 20 years later fled Connecticut for Vermont to escape relentless abuse from neighbouring rebels at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War.

His family was displaced, and the rebels confiscated the Eastman’s livestock, furniture and property.

Benjamin, Sr. was later captured while fighting and jailed in Albany, New York as a Tory Loyalist. Benjamin, Sr. was assigned to work for a Benjamin Miller.

In that time, he had five sons all who were in service of the British army. Once freed, Benjamin, Sr. encouraged his sons Nathan and Benjamin, Jr. to resist the rebels as he had done.

Benjamin, Sr. died on April 1, 1814.

Benjamin, Jr. left home at the age of 17 to join the King’s Loyal Americans under General Jessop. Junior and his brother Nathan organized local Vermonters in preparation for the arrival of the British army assembled to the north by General John Burgoyne.

Like their father they were captured, jailed, and forced to sign an oath of allegiance in order to secure their freedom.

The brothers signed up with the King’s Loyal Rangers. The Rangers provided Capt. Justus Sherwood with many frontier spies and scouts, as well as the advance corps for General Burgoyne’s attack on Vermont and New York.

Benjamin, Jr. saw action in the battles of Hubbardton and Bennington and the eventual British defeat in the Battle of Saratoga. Junior was among the 94 survivors of a regiment of 600.

Benjamin, Jr. made his way to upstate New York and then fled to Canada, where he lived peacefully until the age of 94.

Eastman started the research project last January.

“It was a much bigger undertaking than I anticipated,” Eastman told West Carleton Online from his kitchen table Friday, Aug. 13. “We knew the lineage. But you have to provide supporting documents.”

The Eastmans held a family reunion about eight or 10 years ago at the Carp Agricultural Society Agriculture Hall and a couple 100 relations showed up.

“And there are thousands,” Eastman said. “All Eastmans in North America are all descended from Roger Eastman born in 1610 in Wiltshire, England.”

Royce came to America as a carpenter in Salisbury, Massachusetts until death in 1697.

Eastman is the 10th generation of the family name. Benjamin, Jr. is his direct descendent and the one that qualified him for the loyalist certificate.

“They were stubborn, stubborn British loyalists,” Eastman said. “In the U.S. they were considered traitors. It was God-awful what they went through.”

As mentioned, Eastman knew the lineage, but needed the proof to receive the certificate.

“You need birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates,” Eastman said. “They have to know where the information came from. It has to be verified. Thank goodness for genealogy websites.”

That allowed Eastman to view photos of tombstones and all kinds of other historical records. He also searched the Ontario Archives and National Archives. Eastman visited cemeteries and got information from tombstones.

“Even though we knew we were related, try to find a birth certificate,” Eastman said. “Most of it was found online. The hardest one to find was my great grandfather John. It was hard to find supporting documents because they lived in the wilderness of Canada. It was six months of tracking this down.”

And with a deep dive in a fascinating family history, of course there were some surprises.

“A couple of things,” Eastman said. “At that time child mortality was pretty high. A good quarter of children didn’t survive beyond three years. If a family had a child called David and he died within three months, and let’s say had a child a few years later, thy would often name them David after the first son. Historically names had regularly been passed down. I don’t know how many Benjamins there were. You had to be careful while searching docs.”

Even Dwight has a grandson named Benjamin. But now the work is done, and the Eastman family history is documented.

“It will be a piece of cake for anyone tracking me now,” Eastman said. “I’ve been very interested in genealogy for a long time.”